Prof. Dr. med. Dietrich Tönnis

Sammlung wissenschaftlicher Arbeiten und Vorträge zur Orthopädie

Development of Hip Dysplasia in Puberty Due to Delayed Ossification of the Femoral Nucleus, Growth Plate and Triradiate Cartilage

© Prof. Dr. med. Dietrich Tönnis, Dr. med. Wolfgang Remus

By clicking on a figure an enlarged version of the figure will appear. At the end of the page you will find a PDF version of the paper.

Summary

Besides congenital hip dysplasia, there are dysplasias that do not develop until puberty, causing subluxation of the femoral head to occur late in the skeletal growth period. These dysplasias have various causes. Osteochondritis and osteochondronecrosis have been described.

In the two siblings described in this study, the boy showed a conspicuous delay in the appearance of the femoral ossific nuclei and in the fusion of the triradiate cartilages, which occurred at 16 years of age in the boy and at 13—14 years in the girl. This was preceded by conspicuous structural changes, especially in the posterior triradiate cartilage and acetabular roof but also affecting the lateral growth center of the femoral neck, which was horizontal over two-thirds of its diameter.

We know from animal studies that the growth of the triradiate cartilage increases the diameter of the acetabulum but not its depth. The acetabulum is deepened by pressure from the femoral head. As a result of coxa valga and a prolonged period of acetabular expansion, combined with abnormalities of the superior acetabular rim, the femoral heads in these children eventually subluxated past the acetabular rim. The sclerotic line along the weight-bearing zone of the acetabular roof was shortened and thickened in both children, setting the stage for osteoarthritic changes in later life.

Whenever development of the femoral ossific nucleus is delayed during the first year of life, radiographic follow-ups should be instituted at 8 years of age. A transiliac acetabular osteotomy can enlarge the acetabular roof and improve the acetabular index up to 10—12 years of age. Later a triple pelvic osteotomy can provide further improvement.

Introduction

Hip dysplasia can have various causes. "Congenital hip dysplasia" develops during intrauterine life as a result of deficient amniotic fluid, breech presentation, or other causes (1, 2). Generally it is detected in the neonatal screening examination and is referred for immediate, effective treatment. There are still cases, however, in which congenital hip dysplasia is not diagnosed until the child is older. There are also factors that can delay the onset of hip dysplasia. When one leg is shortened at an early age, the acetabular roof will assume a steeper position on the opposite side, and the femoral head will exert greater pressure on the acetabular margin, hampering its growth. The result is a steep, dysplastic acetabular roof (3).

An abduction contracture of one leg due to previous coxitis can produce a similar tilting of the pelvis, leading to deformity of the acetabular roof on the opposite side (4).

Muscular balance is another critical factor in the development of the femoral neck. Spasticity of the adductor muscles can lead to coxa valga, as can paralysis of the hip abductors. Disuse coxa valga is also known to occur in children following prolonged bed rest. H. Mau has investigated and described this and other hip deformities in some detail (5).

When we follow the spontaneous development of the acetabular roof angle (of Hilgenreiner) in early childhood, we observe deviations that range from borderline-normal to definitely pathologic (6, 7). Most of these deviations are caused by neurologic disorders.

But others are caused by osteochondritis and osteochondronecrosis of the acetabular roof and its ossification centers, which are responsible for the continued growth of the acetabular margin after fusion of the triradiate cartilages. This has been noted by De Cuveland and Heuck (8), Waschulewski (9), and Niethard (10).

Puberty, with its vigorous growth spurt, represents a crisis period for the ossification centers of the acetabulum (10, 11). Mau (12) in 1988 described the pathogenesis of a familial hip dysplasia with "short acetabular roofs" during this period.

In two siblings, we observed unusual areas of irregular calcification that particularly affected the posterior limb of the triradiate cartilage and the superior acetabular rim. This was associated with insufficient broadening of the posterior acetabular margin and acetabular roof.

We feel that it is important to describe the progression of these cases, even though the patients are siblings, since the development of this deformity can be appreciated only in long-term follow-up. Usually this cannot be done in hip dysplasias that are not recognized until a later age. The cause of the dysplasia in the siblings is probably not uncommon. This is illustrated by a third patient whose hip dysplasia was first diagnosed at 19 years of age due to pain.

Case Reports

Case 1

Figure 1 shows the pelvis of the male sibling at 6 months of age. The hips are centered and display a normal AC angle. The patient had no clinical abnormalities. The ossific nucleus of the femoral head had not yet formed by age 6 months, and its development was followed for an unknown period of time. Absence of the nucleus must be considered a special feature of this case and is part of the overall picture. The boy had no neurologic deficits or other appreciable physical defects.

(Fig. 1) Radiograph of a 6 months old boy, hip joints well centered, AC angle normal, but the ossific femoral nucleus had not yet formed at this age and had to be controlled later.

(Fig. 1) Radiograph of a 6 months old boy, hip joints well centered, AC angle normal, but the ossific femoral nucleus had not yet formed at this age and had to be controlled later.

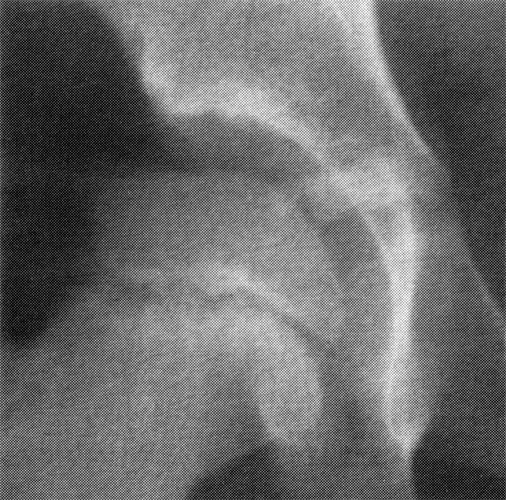

Figure 2A shows the right hip joint at just under 7 years of age, and Fig. 2B shows the left hip joint. In each film the acetabular roof still exhibits a uniform bony structure. The triradiate cartilages on both sides are relatively broad. The growth plates of the femoral neck appear normal on the medial side and relatively broad and irregular on the lateral side. Small defects appear to be present in the superior acetabular rims, at least on the left side.

(Fig. 2A and 2B) At the age of 7 years uniform bony structure, triradiate cartilages relatively broad, growth plates of the femoral neck on the lateral side broad and irregular.

Figures 3A and 3B, enlarged from a radiograph taken at 10 years of age, now show structural irregularity of the acetabular roof with a broadened and somewhat shortened sclerotic line along the weight-bearing zone. The superior acetabular rims are not sharply defined and are not protuberant. The triradiate cartilages still appear very broad. Their margins are undulant laterally and are partially sclerotic. The growth plates in the femoral necks are very undulant, and the adjacent bone shows irregular calcification.

(Fig. 3A and 3B) At 12 years of age, at the right side still broadened triradiate cartilage and ragged superior margin, irregulat calcification in the acetabular roof on both sides and larerally above the acetabular rim with a central ossific nucleus, roofs too short, broad femoral growth plate laterally at the left.

Figures 4A and 4B, taken at 12 years of age, still show a broadened triradiate cartilage in the right hip joint with a ragged superior margin and irregular calcification in the acetabular roof. The triradiate cartilage on the left side has become slightly narrower. In both hips, the superior acetabular rim and the entire posterior margin of the acetabulum should show greater lateral projection. Irregular calcification and structural change are now clearly visible in the superior acetabular rims on both sides. The acetabular roof on each side is too short and shows an increased acetabular index.

(Fig. 4A) At the age of 14 years femoral neck growth plate still not ossified and irregular, also triradiate cartilage, irregular calcification of the posterior acetabular roof with insufficent lateral growth, ossification centers above the lateral acetabular margin still visible.

In Figures 5A and 5B, taken at 14 years of age, the growth plates on both sides still show structural irregularities and are not fully unossified. The structural abnormalities in the superior acetabular rims are even more distinct, with broader decalcification and a centrally located ossific nucleus above the lateral acetabular rim.

Figure 6, taken at age 16, are puzzling in that they appear to indicate an osteochondritic lesion in the acetabular roof above the horizontal posterior triradiate cartilage. A number of small, rounded calcifications are visible on both sides. The decalcified area above the superior acetabular rim has become smaller, while the ossific nucleus has grown. The femoral neck growth plate and the triradiate cartilage on the left side are not yet closed.

(Fig. 6) Radiograph at age 16 years. All growth plates and the acetabular roof are fully ossified and both femoral heads are lateralized. There is increased calcification of the short weight-baring zone and no congruence between the femoral head and the shallow acetabulum.

In the radiograph in Fig. 7, taken at 16 years of age, the triradiate cartilages are fully ossified. Both femoral heads are lateralized and are exerting greater pressure on the shortened lateral rim of the acetabulum, manifested by increased sclerosis of the weight-bearing zone in that area. There is also narrowing of the lateral joint space on the left side. An indentation is visible in the bony surface above the lateral acetabular rim, and we still observe slightly increased calcification due to the growth disturbance of the acetabular rim.

Also, marked incongruity is apparent between the femoral head and acetabulum in both joints. The acetabula have a greater radius and are shallower. The acetabular fossa forms a broad, deep arc that blends smoothly with the acetabular roof without the usual step. This finding appears to be a feature of this condition.

The young man was 19 years old when last seen. He was free of pain and was very active athletically. It is reasonable to expect, however, that premature osteoarthritis will ensue. When complaints appear, a triple pelvic osteotomy would be indicated to improve the acetabular coverage of the femoral heads.

Case 2

The boy’s sister was diagnosed elsewhere with hip dysplasia after birth and was treated with an abduction pillow for several months. When we first saw her at 2 years of age (unfortunately the radiograph is no longer available), we observed normal maturation of the hips. The patient had no neurologic abnormalities or other findings.

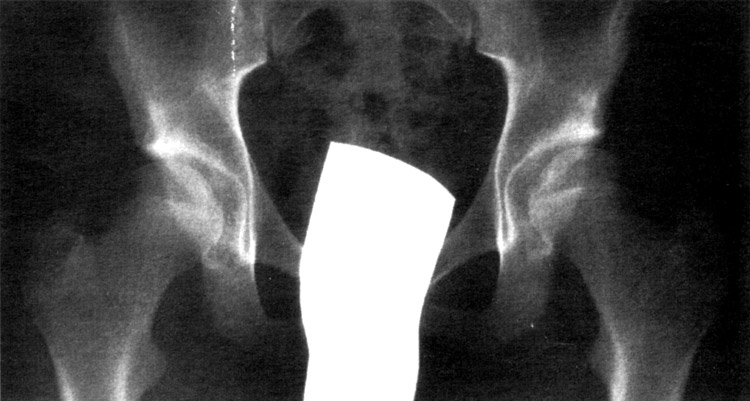

Figure 8 shows the pelvis at age 5 years, 4 months. The growth plates of the femoral necks show a marked horizontal orientation, but on each side there is adequate femoral head coverage by the acetabular roof with a broad sclerotic line, which is a little steeper on the left.

(Fig. 8) Pelvis of a girl at age 5 years, 4 months. The growth plates of the femoral necks show a horizontal orientation, but there is adaequate femoral head coverage with a broad sclerotic line.

(Fig. 8) Pelvis of a girl at age 5 years, 4 months. The growth plates of the femoral necks show a horizontal orientation, but there is adaequate femoral head coverage with a broad sclerotic line.

Figures 9A and 9B show that the triradiate cartilages are not yet fully ossified at 12 years, 6 months of age. The triradiate cartilage in the right hip is very undulent in the horizontal plane. The acetabular roof shows irregular calcification at its inferior border, which is more pronounced on the right side than on the left. The superior rim of the right acetabulum shows a steeper lateral slope than on the left side, as if due to a growth abnormality of the superior rim. A uniform sclerotic line is not present along the weight-bearing zone of the right acetabulum; it is somewhat better developed on the left side.

At 12 years, 6 months the triradiate cartilages are still broad and the right hip very undulate. There is no sclerotic weight-baring zone and no marked lateral acetabular rim at the right. The femoral growth plates are not yet fully ossified in both sides.

In Fig. 10, taken at 15 years of age, the triradiate cartilages are completely ossified and the weight-bearing zones show normal definition but are somewhat shortened. The femoral heads show deficient acetabular coverage on both sides, and the CE angle is decreased. Again, the sclerotic line blends smoothly with the deep acetabular fossa without a step. There is a distinct bony indentation above the acetabular rim, smaller than that visible in the brother.

(Fig. 10) At the age of 15 years there is a complete ossification and the weight-baring zones show normal definition, but are shortened and the femoral heads not fully covered, even the left one, which appears less pathologic in Figure 8. Here the subcapital coxa valga may have been of additional influence.

(Fig. 10) At the age of 15 years there is a complete ossification and the weight-baring zones show normal definition, but are shortened and the femoral heads not fully covered, even the left one, which appears less pathologic in Figure 8. Here the subcapital coxa valga may have been of additional influence.

Case 3

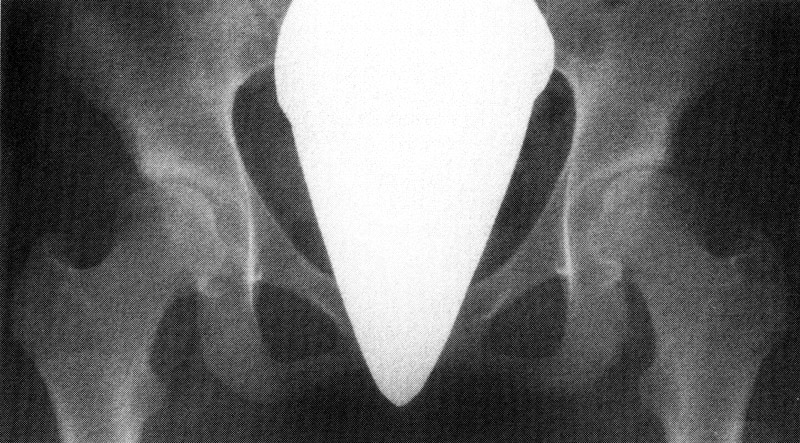

Figures 11A and 11B illustrate what we believe to be the end result of a similar process. The patient presented at 19 years of age with predominantly left-sided hip pain. He was noted to have bilateral coxa valga. Examination also revealed lumbarization of the first sacral vertebra with spina bifida. No other abnormalities were found. Elsewhere a varus osteotomy was performed on the left side to improve femoral head coverage.

This patient, too, showed a horizontal orientation of the femoral neck growth plates (Fig. 11A) and a short acetabular roof with increased sclerosis, which had an unusual ragged shape on the left side. As in the siblings, the weight-bearing zone on each side blends smoothly with a very broad acetabular fossa, with no intervening step. A lateral bony indentation is present above the superior acetabular rim, as in our first two cases. A varus osteotomy caused excessive lateral loading of the femoral head, and the acetabular roof was still too short and steep. Lateral rotation of the acetabulum with a triple pelvic osteotomy would have been a better option and would have centered the load on the femoral head.

Discussion

The first two cases (brother and sister) involved a disturbance and delay of ossification. In the boy’s case, the ossification centers of the femoral heads had not yet appeared by 6 months of age. The triradiate cartilages in this patient did not fully ossify until 16 years of age. Presumably this occurred in the girl at about 14 years of age.

The irregular calcification and structural irregularities of the triradiate cartilages are suggestive of osteochondritis and osteochondronecrosis involving the acetabular roof and also the superior acetabular rim.

Animal studies in which acetabular growth was observed after experimental dislocation of the femoral head have shown that growth arising from the triradiate cartilages expands the outer diameter of the acetabulum but does not increase its depth (13, 14). This requires pressure from the femoral head directed toward the center of the acetabulum. During the prolonged growth period in these children, it appears that the acetabulum grows mainly in its outer dimensions (diameter) while the centering pressure steadily declines, due in part to the horizontal orientation of the epiphyseal plates in the femoral neck and to the pressure exerted on the superior acetabular rim. As a result of these factors, hip dysplasia and subluxation develop during the latter part of the growth period. These changes were more pronounced in the boy than in his sister. Ossification disturbances and delays also involved the horizontal triradiate cartilage and the posterolateral region of the acetabulum.

When we looked for similar cases in the literature, we found only a few. Niethard also describes bony and cartilaginous irregularities in the acetabular roof. The patient in his Fig. 1B exhibits changes similar to our patients. Niethard distinguishes between intercurrent osteochondritis of the acetabular roof, osteochondritis of the acetabular roof with a bony superior rim defect, and osteochondronecrosis of the acetabular roof. The radiographs in Fig. 4A and B do not document the progression of the changes, but the end result is the same.

In Mau’s children with "short acetabula", his Figs. 2C, 4C, and 4D show small, faint areas of irregular calcification in the acetabular roof. The child in Fig. 4 still does not exhibit femoral ossific nuclei at 4 months of age - another important sign.

Conclusions

Hip dysplasia may follow the course described here, not becoming evident until after 10 years of age. When the appearance of the femoral ossific nuclei is delayed, the hip joints should be periodically examined for growth disturbances from 8 years of age until the pubertal growth period. These disturbances are probably more common than has been assumed, because radiographs are not obtained during this period in the absence of pain. If pain occurs at 19 years of age, as in our third case, it is generally attributable to prenatal causes.

A transiliac acetabular roof osteotomy (2, 15, 16, 17) can provide broad, horizontal coverage of the femoral head up until 10 - 12 years of age. Thereafter, the triple pelvic osteotomy (2, 16, 18) is the best corrective option. Due to the relatively short sclerotic weight-bearing zone, however, the acetabulum should not be rotated too far - only until it is horizontal. Whenever possible, moreover, the femoral head should project below the acetabular roof with a migration percentage (18, 19) of 10 - 15%.

References

- Tönnis, D. (editor), Legal, H., Die angeborene Hüftdysplasie und Hüftluxation im Kindes- und Erwachsenenalter. Heidelberg: Springer; 1984

- Tönnis, D. (editor), Legal, H., Graf, R., Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults., Heidelberg: Springer; 1987

- Mau, H., Disturbances of growth at the femur in leg-length differences of children. [in German], Beih. Z. Orthop. 1958; 90:107

- Baake, M. Tönnis, D., Secondary dysplasia of the hip-joint following arthrodesis of the opposite hip in abduction [in German]., Z. Orthop 1974; 112:78-95

- Mau, H., Factors influencing growth in the normal and abnormal hip joint. [in German], Arch. Orthop. Trauma surg. 1957; 49:427-452

- Tönnis, D., Brunken, D., Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of the X-rays in children and adults. [in German], Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1968; 64:228-237

- Exner, G.U., Kern, S.M., Natural course of mild hip dysplasia from young childhood into adulthood. [in German], Orthopädie 1994; 23:181-184

- DeCuveland, E., Heuck, F., Osteochondropathy of the anterior iliac spine and disturbance of the apophysis of the lateral acetabular margin. [in German], Fortschr. Röntgenstr. 1951; 75:430

- Waschulewski, H., Centers of acetabular ossification and periarticular ossifications, osteochondropathy of the anterior iliac spine. [in German], Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1967; 62:273-290

- Niethard, F.U., Osteochondrosis and osteochondronecrosis of the roof of the acetabulum. [in German], Z. Orthop. 1984; 122:94-98

- Imhäuser, G., Puberty as a critical period of the hip joint. [in German], Z. Orthop. 1974; 112:577-580

- Mau, H., Familial hip dysplasia with short acetabular roofs. [in German], Z. Orthop. 1988; 126:156-160

- Azuma, H., Kako K., Growth of human acetabulum: with a comparison of cartilaginous proleferation in acetabular and triradiate physeal cartilages., Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 1984; 58:583-590

- Ooishi, T., Experimental study on the etiology of pathogenesis of acetabular dysplasia in congenital dislocation of the hip. Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 1990; 64:958-975

- Wiberg, G., Shelf operation in congenital dysplasia of the acetabulum and in subluxation and dislocation of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Am) 1953; 35A:65-80

- Tönnis, D., Treatment od residual dysplasia after development dysplasia of the hip as a prevention of early coxarthrosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 1993; 2:133-144

- Tönnis, D. Brüning, K., Heinecke, A., Lateral acetabular osteotomy., J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 1994; 3:40-46

- Tönnis, D. Arning, A., Bloch, M. Heinecke A., Kalchschmidt K., Triple pelvic osteotomy., J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 1994; 3:54-67

- Reimers, J., The stability of the hip in children., Acta Orthop. Scand 1980; (suppl): 184.

| Download | |

|---|---|

| Development of Hip Dysplasia in Puberty Due to Delayed Ossification of the Femoral Nucleus, Growth Plate and Triradiate Cartilage | PDF (x.x MB) |